Hurricanes, aka tropical cyclones, are one of the most extraordinary and potent forces seen in nature. One of the world’s most at-risk areas is the east coast of America, but what lessons are there for the UK?

Hurricanes, aka tropical cyclones, are one of the most extraordinary and potent forces seen in nature. One of the world’s most at-risk areas is the east coast of America, but what lessons are there for the UK?

Hitting the US east coast in September 2022, Hurricane Ian was the third costliest weather disaster on record, and the deadliest hurricane to hit Florida since 1935.

Such events prompt us to reflect on how we are progressing in our management of coastal adaptation in the UK.

In this article we explore hurricanes, how they have changed in the 21st Century, and what they can teach us.

How hurricanes are generated

When seas reach temperatures of 25.5°C and above, evaporation from the water surface transfers energy vertically upwards.

This creates an area of rising warm air with a zone of low pressure at its base, just above the surface of the water, which draws in more air. The earth’s rotation then causes these convection currents of air to circle, spiraling up and driving staggering wind speeds.

Tropical seas off the east coast of America reach sufficient temperatures for hurricanes, but in the UK our seas are too cold to provide the energy needed.

How hurricanes cause damage

Although violent wind speeds are often thought to be the main cause of hurricane damage, the vast majority of fatalities are due to water.

Between 1963 and 2012, 49% of hurricane fatalities were attributed to storm surges; the primary causes of fatalities in hurricanes Katrina, Betsy, and Sandy.

These surges are caused by sudden rises in sea level, from both the zone of low pressure, and sea water built up by the hurricane wind speeds.

Vulnerability to hurricane storm surges varies significantly from location to location.

In areas with steep topography, such as the coastline of Florida, far more water must be displaced to cause significant damage than in low-lying areas.

A prime example of this was the way the impact of Hurricane Katrina varied between US states in 2005.

- Florida storm surges reached around 1.64 m and caused damage that mostly affected infrastructure, with only six fatalities from direct storm impacts.

- New Orleans storm surges reached around 5 m and caused catastrophic damage and around 400 direct fatalities. This, despite the majority of the population having been evacuated from this low-lying and flatter area.

However, the lines along which certain areas may be considered to be less at risk to hurricanes are becoming blurred as sea levels rise.

Along the east coast of America, sea level rise induced by climate change is predicted to amount to around 0.4 m in the 21st century. Under storm-surge conditions, this can have an increasingly significant effect on storm surge severity, making catastrophic events far more common.

This also may not be the only way in which the east coast of America will face worsening hurricane impacts in the years ahead.

Analysis of historical records

Dr Angela Colbert of NASA stated in 2022 that global climate models are forecasting more intense rainfall levels as a result of hurricanes.

There is no consensus on whether global storm frequency may change, but there is a greater chance that each individual hurricane will be of increased intensity.

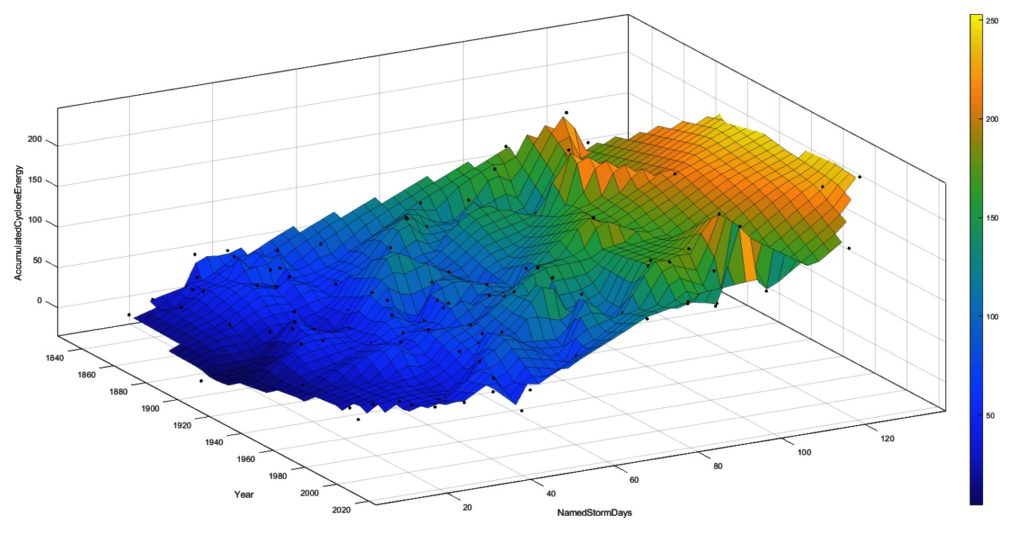

Analysis of publicly available data held by Colorado State University on tropical cyclones and storms in the North Atlantic has added helpful historical context to the present situation in the US.

- Under many metrics, frequency and intensity of hurricanes has increased annually.

- The frequency of storm days (both of hurricanes and tropical storms) appears to have generally increased after 1940 for the majority of years recorded.

- The largest proportion of years exceeding 100 units of accumulated cyclone energy occurred since 2000.

Accumulated cyclone energy and frequency of major North Atlantic tropical cyclone (hurricane) days observed over time

Policies and politics

Analysis of historical records alone can’t predict the future trajectory of hurricane characteristics, but it can show how out of step with reality US Coastline housing and planning policies are.

US State policy still fails to dissuade development in areas with severe hurricane risk, even after catastrophic events such as Hurricane Katrina, and in the face of increased event frequency and severity over the past 100 years.

It is thought that almost 10 million more people will have moved to hurricane-risk areas between 2010 and 2025.

According to Dr Kerry Emanuel of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the politicisation of insurance processes is largely responsible.

- Wind-based damage is mostly privately insured against, with heavy state-level regulation, but it is still often politicised. Inhabitants of coastal areas often lobby to introduce caps to insurance premiums and in the event of disasters it is taxpayer money that has to come to their aid rather than money from insurance sources.

- Water-based damage, despite coming under Federal Flood Insurance rather than private companies, State representatives for coastal areas are still able to lobby to lower insurance premiums. Again, this means prospective inhabitants to coastal areas do not have to face a financial ‘warning cost’.

- Relocation and development of settlements to less-at-risk areas is not sufficiently incentivised in the aftermath of hurricanes to encourage rebuilding elsewhere.

In the UK, we also have lessons to learn.

Whilst not subjected to hurricanes, our coastline is still vulnerable to storm-surge events. This was seen lethally in the 1953 North Sea Flood, and more recently in the 2013 surge of Cyclone Xaver.

Flood risk nationally has been greatly reduced over the last 30 years with flood defences, but the Environment Agency estimates that the number of developments located in flood-risk areas will double at a minimum by 2055. Assessing governance, and updating both policy and implementation is absolutely essential to reduce risk levels further.

In 2021, a Defra report highlighted notable shortcomings in the UK’s current policies on coastal flooding. Politicisation of policy may not be the primary problem, unlike the situation in the US, but a lack of cohesiveness between differing bodies results in responsibilities for reduction of flood risk being critically unclear.

Current shortcomings have been highlighted clearly in examples such as the proposed ‘decommissioning’ of the entire Welsh village of Fairbourne.

The last word

We are on a collision course with nature

It is generally politically far easier for policy makers to put measures in place to remediate a disaster after the event, than to avert a future one.

Until this changes, the east coast of America, and perhaps the coast of Britain, remains on a collision course with nature.