Our hydraulic models have an eye for the detail, but this planner’s guide won’t give you an earful of jargon.

Our hydraulic models have an eye for the detail, but this planner’s guide won’t give you an earful of jargon.

The limits of regulator flood maps

Flood maps hosted by the environmental regulators of England, Scotland and Wales can provide the basis for assessing planning applications with regard to flood risk.

These flood maps visualize the results of hydraulic modelling studies of watercourses, mapping inundated areas for certain-likelihood storm events.

The modelling studies used come from a wide range of sources. They may be the product of very coarse, strategic studies for a region, or much more detailed hydraulic models for a particular stretch of river or for a particular development.

The results from large-scale, coarse modelling, whilst useful for strategic land planning, often do not represent flood risk sufficiently well for individual sites. River and floodplain features are poorly represented and broad-stroke techniques are used, resulting in estimates of risk that can be significantly inaccurate.

Reasons that often lead to under- or over-representation of flood risk include:

- culverts not being explicitly modelled

- defence or other embankment crest levels (which determine breach levels) not being captured

- channel conveyance capacity (particularly for small watercourses) not being well estimated

- watercourse flow estimates for storm events being inaccurately calculated.

The image below shows how coarse terrain mapping (rather than a river-channel survey), having missed the low points in the topography, has resulted in a flood map that is detached from the actual course of the river.

The advantages of detailed hydraulic modelling

Detailed hydraulic models for specific watercourses or developments have crucial advantages over coarse strategic studies for flood risk.

The benefits of more detailed flood modelling for developments mean that it is often used prior to planning applications and can be required by environmental regulators.

These bespoke models can provide a clearer and more robust understanding of flood risk for a development in a number of ways, such as:

- refining flood extents for critical-return-period storm events, potentially redefining areas within a potential site, within and outside the flood zones

- helping determine finished floor levels for a development with more confidence, potentially improving flood resilience

- quantifiably assessing a proposed development’s impact on third-party flood risk

- understanding residual risk to developments from blockages in watercourses or breaching of defences

- accounting for uncertainties in the modelling process through sensitivity testing and including climate-change scenarios in outputs

- providing robust evidence to the regulator, resulting in more efficient consent of applications on the grounds of flood risk.

Types of hydraulic modelling

The requirements for hydraulic modelling can vary greatly for a development.

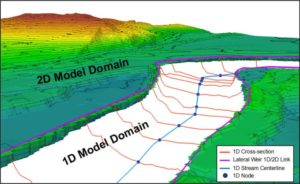

- 1D models can provide simplistic solutions, giving estimated flood levels in a watercourse, which in turn can be inferred across the floodplain.

- 1D/2D models can represent features within the floodplain, by linking the 1D model of the watercourse with a 2D terrain model of the surrounding land.

1D-2D models give a more complete and rounded understanding of out-of-channel flows and storage across a floodplain, giving more realistic depths and allowing for the estimation of velocities, and therefore hazard ratings across the mapped area. This additional information is usually required for larger and more complex developments, where it is necessary to understand existing flood risk across the development site in detail and potentially to assess post-development impacts.

*Image credit to D. Gilles, et. al., Water, 4(1), 85-106 (2012)

What modelling studies require

The data and timescales required for modelling studies inevitably vary according to the complexity, detail and scale of the project.

A typical hydraulic model will require a watercourse survey, covering river sections and any structures within the river channel. This forms the basis of the 1D watercourse model, unless a previous model has been carried out in the same location from which data can be recycled.

The 2D floodplain will then typically be represented by one of two data sources:

- digital terrain data, such as LiDAR, which now has good coverage and is commonly free to access across the UK

- a topographical survey, depending on the coverage of other sources, and the level of detail required.

Results can usually be issued to a client within five to eight weeks of the commissioning a river-channel survey.

Our approach

WHS specializes in hydraulic modelling projects. We have significant experience in the delivery of projects of all types and sizes, delivering outputs that are meaningful to clients and acceptable to regulators.

We liaise early with the regulator to obtain buy-in with our approach to the modelling. We also work with the client to provide mitigations and solutions to manage flood risk for the development where appropriate.

The East West Rail project (described in the accompanying article) is an example of a modelling project in which we assessed the drainage and flood risk along the Oxford to Bicester section.

The last word

In hydraulic modelling studies, nothing is as significant as relevant local detail to boost confidence in the design of a development.